The Gravediggers Didn’t Have To Triumph

Genocidal dictatorships comprised of ‘sorcerer’s apprentices and windbags’ are not inevitable. Excerpts from The Gravediggers: The Last Winter of the Weimar Republic

***Please take out a membership to support the light of truth.***

“The gravediggers didn’t have to triumph.”—Rüdiger Barth and Hauke Friederichs, The Making of, The Gravediggers

I woke up Tuesday morning to a crime scene. My highlighter had bled all over my duvet cover, as I tried to work through the night to finish the final pages of The Gravediggers: The Last Winter of the Weimar Republic. I’ve been reading the book for a couple of months, but repeatedly pressing pause to read the reference books used to lay the foundation for The Gravediggers.

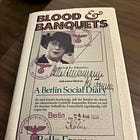

That’s how I was able to bring you Bella Fromm’s diary:

That’s how I knew who Dorothy Thompson was and could bring you this report:

It’s also how I knew about the Keppler Circle, the elite businessmen who propped up Hitler, Himmler, and genocide, and were later executed by hanging in Nuremberg.

I was confident when writing about how fake racist news was deployed on Germans to make them support the Nazi regime.

But more than anything, I heard my ancestral voices calling out to me:

“Keep writing. Tell our stories. Warn America. Tell the truth.”

I heard the ancestral voices in German.

“Schreiben Sie weiter, erzählen Sie unsere Geschichten, warnen Sie Amerika und verbreiten Sie die Wahrheit!”

I am first generation German-American. If ever I had a duty to warn, this is it.

The Gravediggers authors Rüdiger Barth and Hauke Friederichs offer a day by day account of the lead up to Adolf Hitler being made Chancellor of Germany. The book documents each day from November 17, 1932, until January 30, 1933, the day Hitler took power.

The voices call out to us from the grave, because they know what can happen when good people do nothing.

The narrative is told through the eyes of the reporters in Berlin, the politicians, the gloomy diary of Joseph Goebbels, trade union leaders, playwrights, communist leaders, diplomats, poets, authors, newspaper headlines, Nazi wives, the son of Germany’s president, and Hitler himself.

As the authors explain in The Making Of epilogue, they came to the idea of focusing on the last ten weeks of the Weimar Republic because they learned of the battle between Franz von Papen and Kurt von Schleicher, the previous chancellors before Hitler.

“At school we were simply taught to think of Papen as the Republic’s ‘gravedigger’, but it soon became clear to us how complex their struggle had been between late 1932 and early 1933, all of which were co-responsbible for ending the first Germany democracy.”

They had also been watching House of Cards. They realized that what had happened in the last days of the Weimar Republic mirrored the television series about a diabolical, power-hungry politician. The difference was, their story was real, with consequences that left our world permanently scarred.

They constructed the book “like a documentary montage”, where the characters speak for themselves.

“It was too banal to say that Hitler’s seizure of power was by no means inevitable. Yet it wasn’t until we came to write this book that we understood how cunningly, selfishly and unscrupulously the major German politicians of the age had behaved. How many opportunities there had been to bring down the Nazis. The gravediggers didn’t have to triumph.”

And yet, they did. Hitler and Goebbels told Germany and the world what their diabolical plans were, and yet, they triumphed. Until they committed suicide a day apart in 1945.

I didn’t go looking for the parallels to our dilemma, but they were there on each page.

On the day Hitler was named Chancellor, his supporters created a sea of torches and swastika flags were hoisted.

It was Goebbels — the club-footed ‘raging dwarf — who’d come up with the torchlight procession. Goebbels, the only one in Hitler’s inner circle who appeared to truly love him, claimed half a million people were there. The British embassy said it was more like 50,000. Columnist Bella Fromm, who had given Goebbels ‘the raging dwarf’ nickname, said it was 20,000.

They were lying about crowd size from the very beginning.

The most important thing to know about The Gravediggers is Hitler was on his way out. The National Socialist German Workers’ Party (NSDAP) was fracturing, there was infighting and Hitler refused to draw together a parliamentary majority that would support him as chancellor. After President Paul von Hindenberg appointed Gen. Kurt von Schleicher chancellor — two weeks after Franz von Pappen announced his cabinet’s resignation — devotion to the Fürher had become perfunctory — a performance of solidarity.

The business elite still backed him, however.

“Democracy is the most complicated form of politics.”—The Gravediggers

Like a schemer in a Shakespearean tragedy, von Papen was a monarchist, who dreamed of staging a coup, after being removed from power.

Germany in the winter of 1932 was cold and poor. The economy had bottomed out. German politics was suffering an ‘unprecedented paralysis.’

Pause here for a moment and let’s reflect on America in 2024 — our economy under Joe Biden is the envy of the world. But a professional propagandist backed by the terrorist state of Russia and a complicit media has blanketed the US with lies, so millions of people do not know the economy is roaring. Their cult leader tells them terror stories, and they believe him.

Hitler tells the German people he’s going to make Germany great again, and they believe him.

As with my Bella Fromm report, what follows are excerpts and commentary.

Kaiser Adolf

Thursday, November 17, 1932: American ambo Frederic Sackett had written to the State Department that Hitler was ‘one of the biggest show-men since P.T. Barnum.’ The Americans didn’t like von Papen because he’d been a military attaché in Washington during the first World War, ‘secretly building up a spy ring for the Germans.’

As newspaper headlines wondered if Hitler’s time had finally arrived, Bella Fromm knew that he offered ‘nothing that bodes well for decent people.’ She’d nicknamed him ‘Kaiser Adolf.’

As she watched the power plays behind the scenes, she knew everyone was underestimating ‘the radical movement’ of the Nazis.

We see Berlin through the eyes of the writer Abraham Plotkin, whose family fled the ‘dark shadows of terror’ in Tsarist Russia. Plotkin, who would later run rescue operations, visited the poor in Berlin — the people who lived in Russian-owned slum buildings, who couldn’t pay rent and eat, who were sick and freezing.

We read the diary of Goebbels, who became the Minister of Propaganda and Enlightenment, who spends many days brooding, always thinking of his beloved Fürher. He played the accordion for Hitler, ‘the only indulgence Hilter permitted himself after a dogfight.’

Saturday, November 19, 1932: Hindenberg received a letter from hundreds prominent industrialists throwing their support to the NSDAP.

Tuesday, November 22, 1932: Hitler feels attacked, because he can’t get his ‘mitts on power without finding coalition partners.’ He and Goebbels unwind at the opera with some Wagner. Goebbels wrote: “Wagner’s eternal music gives all of us renewed strength and endurance. At the great Awake chorus we all felt our hearts swell.’

I’ll just leave that right there.

Wednesday, November 23, 1932: Sackett’s British colleague, Sir Horace Rumbold, refuses to meet with Hitler or any other Nazi. A synagogue’s windows were smashed for the third time in days. Police suspect Nazis and announce they are boosting patrols.

As the authors introduce us to the events of each new day, they open with headines from the Nazi paper, the communist paper, and major Berlin dailies. It’s so interesting because you can read through the propaganda of the fascists, the anti-fascists, and then get more reliable news from the various daily papers not aligned with either the NSDAP or the communist movement.

On November 24, we learn that Hitler ‘was excited about the Ku Klux Klan, the skyscrapers and the anti-semitic Henry Ford. That was more or less all he knew of America.’

We also learn he was still seething from an interview he did with American reporter Dorothy Thompson for Cosmopolitan. She wrote a book titled I Saw Hitler where she noted the ‘startling insignifance of this man who set the world agog.’ She described him as ‘almost faceless, whose countenance is a caricature, a man whose framework seems cartilaginous, without bones… ill-poised and insecure… the very protoype of the little man.’

She wrote his dark, grey eyes ‘have the peculiar shine’ of ‘geniuses, alcoholics, and hysterics… a man in a trance.’

I recall filmmaker Melissa Jo Peltier describing Trump as the most insecure man she’d ever met.

On November 24, we also learn Goebbels is miffed for being referenced as an agent of Moscow, and at a Hermann Goering press conference, he yells at journalists that they hadn’t given Hitler a chance, and only he can rescue the German people.

“Only I can fix it…”

Abraham Plotkin was at a saloon chatting with a prostitute. She asked him if he read Döblin’s Alexanderplatz. He told her that’s why he was in the neighborhood. She quoted a line that Döblin said ‘that time is a butcher and that all of us are running away from the butcher’s knife.’ She said in the meantime, she wants to live and asked him to buy her another schnapps.

Friday, November 25, 1932: Red-haired Texan, Hubert Renfro Knickerbocker, a reporter for the New York Evening Post, told his editor that ‘Hitler is a homosexual, effeminate corporal with a hypersentive political olfactory nerve.’

At 5:10 pm that day, an SA officer died in a violent clash. The Nazis described him as the ‘twenty-eighth martyr in our struggle against Marxism in Berlin.’

!

Maybe because he was an American, a good listener, and well informed, but people liked talking to Abraham Plotkin. People on the streets were warning of bloodshed that would spread like wildfire.

Punch-ups

December arrives with pages and pages of political turmoil, palace intrigue, growing anti-semitism, and ‘punch ups between the Nazi and the Sozis.’ Food is rotting on shelves, because people are too poor to afford it, not because there’s a shortage.

Poetry is strewn throughout this section like dead leaves on snow — dreary, with little hope.

Goebbels spends many days hand-wringing over the bad shape of NSDAP finances.

Saturday, December 10, 1932: A foreign press secretary said a doctor said that former Nazi party leader Gregor Strasser said:

“I am a man marked for death… Germany is in the hands of an Austrian who is a liar of genius, a former officer who is a pervert, and a club foot. The last is the worst of all. He is Satan in human form.”

The authors Barth and Friederichs note the ‘pervert’ was Ernst Röhm, the head of the SA, whose homosexuality was an open secret.

I had to jump ahead and find out what happened to Strasser, who split with Hitler because he was part of the leftist wing of the Nazi party. He was murdered on June 30, 1934, in a purge known as the Night of the Long Knives.

By mid-December, Chancellor Kurt von Schleicher, who had offered Strasser the Vice Chancellor position, hoping to divide and weaken the party, had gotten some good news. The Treaty of Versailles, which had ‘shackled the Weimar Republic for so long, was slowly being watered down.’ A diplomatic breakthrough, and an agreement that the German Reich should be granted equality of military rights was declared. The condition that the security of all nations be guarenteed. von Schleicher thought this would help diffuse the ‘radical right’s arguments… as more soldiers could help defend the Republic from its enemies on the home front.’

Goebbels spent days on trains, ‘coaxing functionaries…to swear allegiance to Hitler.’ We also learn Hitler has a weakness for back-channel communication.

“I’m going to the United States. Nothing good is going to happen here for a long time.”—Ernst Lubitsch

Thursday, December 15, 1932: von Shleicher gives a speech where he makes the mistake of being honest — revealing who he is in complex sentences. He let the German people know he planned to serve only briefly during Germany’s hour of need, and denied any intention of establishing a military dictatorship.

“One cannot sit comfortably on the point of a bayonet.”

He promised to pursue only one goal: job creation.

Then he wandered onto unexpected turf, declaring himself a devotee of neither capitalism or socialism, calling himself a ‘social general.’

Goebbels gloated, knowing von Schleicher would not be long for the office, and industrialists were shocked, hoping for a return to von Papen’s industry friendly policies, his remarks ‘about capitalism going down like lead balloons.’

INTERMISSION

I want to share with you every word I highlighted, but by now, I’m sure your eyes are growing weary so I will just pick and choose from the best of the pink, yellow, and orange lit up sections. (Maybe take a break, rest your eyes, and come back after some tea.)

Goebbels and Hitler saw there in as von Schleicher misfired and went on a charm offensive.

von Papen returned and began taking back room meetings with von Hinderburg’s son, Oskar.

No one liked anyone or trusted anyone, except Hitler and Goebbels, but they made these deals with overtly dangerous men for the pursuit of power, greed, corruption, and racism.

As the pages turn, more sad poetry, and mutiny among SA divisions, mostly over unapproved purchases of potatoes for uniforms. Brownshirts were taking back their oaths of allegiance.

Abraham Plotkin was so bored at a Nazi rally he left.

The National Socialists were hemorrhaging votes and poet Oskar Loerke was dreaming of vast, sinking ships.

Monday, December 19, 1932: ‘Infectious diseases on the rise’… people could not afford to bathe. Germans were drinking to forget. There were a million abortions a year, and thirty thousand women died during botched procedures.’ Hitler lost 40 percent of his following. More SAs mutinying. NSDAP 14 million marks in debt. The Keppler Circle of elite businessmen had some good news: ‘Hindenburg and Schleicher were on the rocks.’

Back rooms in villas were offered for clandestine meetings with Hitler.

SA men were going hungry, but still being forced to pay their dues, causing more signs of party collapse.

More street brawl ‘punch ups’ — all strenuously denied by the NSDAP.

Fairy Lights

Thursday, December 22, 1932: ‘Strings of fairy lights glowed in the dusk.’

All throughout Berlin, reports of people committing suicide. Fathers ashamed they could not provide for their families. Desperate times.

Hitler made a record. An advert in the Nazi newspaper said it would make ‘a wonderful Christmas present for any National Socialist. Price 5 marks.’

Brooding Goebbels

Goebbels was ‘feeling deeply lonely.’ Magda, his wife, also worshipped Hitler, and her ‘brazen flirting’ embarrassed him. He had so few friends, because he was sure everyone was jealous of his ‘success and popularity,’ he wrote in his diary. In addition, Magda was ill.

He spent ‘a sad Christmas’ with his bodyguards.

Franz von Papen was hellbent on revenge, plotting to get rid of Schleicher.

Hitler listened to the sound of his own voice in the Bavarian mountainside, thanks to Goebbels, who recorded his speeches on gramophone records.

Hitler could wallow in his own rhetorical gifts whenever he felts so inclined.

The Twilight of Doubt and Despair

Saturday, December 30, 1932: A member of the Reichsbanner wrote of ‘the twilight of doubt and despair’ — ‘an army that could withstand 1932 cannot be beaten in 1933.’

Schleicher sent a New Year’s telegram to Franz von Papen, with ‘much love to my dear Fränzchen.’

The authors wrote: ‘Who would send a telegram to revenge-plotting rival?’

Schleicher evidently.

I Wish You Power

Midnight. Zero hour, 1933: Goebbels shook the Führers’ hand. He gazed at him and said: ‘I wish you power.’

New Year’s Day 1 am — a member of the Hitler Youth named Walter Wagnitz was knifed in the gut.

Tuesday, January 3, 1933: Newly released from prison, reporter Carl von Ossietzky wrote that at that beginning of 1932, the ‘Nazis seemed on the verge of a dictatorship, and the air was full of the stench of blood. By the end of it, Hitler’s party had been shaken… long knives were put quietly back in their box.’

He referred to Goebbels as a ‘hysterical cheese mite.’

In Hamburg, an assassination attempt was made on a Jewish newspaper editor. The bullets missed and went through his hat. He had written articles after a visit to the USSR, condemning the way Jewish people were treated. The communists were blamed for the attempt on his life.

Hatred Would Reign

Abraham Plotkin was horrified at how Goebbels weaponized the death of Walter Wagnitz, the knifed Hitler Youth. He railed against the Jews, as ‘men and women were cheering themselves hoarse.’

He couldn’t believe how ‘Goebbels had exploited the boy’s death to whip up the crowd.’

Hatred would reign, if the Nazis came to power.

Saturday, January 7, 1933: Tens of thousands of people joined the funeral procession for Wagnitz, while singing the Nazi anthem — the Horst Wessel Lied.

“The Nazis didn’t need facts. They didn’t need truth to goad the mob into a rage… the narrow minded crowd was easily seduced.”—Abraham Plotkin

Thursday, January 12, 1933: Hitler no longer believed he would become chancellor.

A doctor in Lippe prints his resignation letter from NSDAP because he found the leaders to be ‘little political charlatans, Cagliostros, sorcerers’ apprentices and windbags.’

“One cannot fight the battle for freedom with the souls of slaves.”—former regional NSDAP leader

The editor of a Berlin daily noted the charm offensive was failing to bear fruit.

“Returning from his heroic struggle in Lippe, all Hitler has actually brought home is a fly impaled on the tip of his sword.”—Theodor Wolff

Days pass and von Schleicher believes Hitler is no longer interested in power. Supposed allies view him as a ‘rabble-rousing vulgarian.’

More secret meetings. No one trusts anyone. von Papen wants revenge, and he will use Hitler to get it.

Joachim von Ribbentrop arranges a meeting with Oskar von Hindenburg, the president’s son, Hitler, and other schemers.

Riff-Raff Who’s Read Nietzsche

More marching brownshirts screamed slurs at Jewish people, which made up less than one percent of the German population in 1933, but about 32 percent of the population of Berlin.

The Nazis were escorted by police, who did nothing about the violent threats.

A giant of literary journalism Alfred Kerr called Hitler ‘riff-raff who’s read Nietzsche.’

Kerr’s name was on a list of banned writers published in the Nazis official newspaper, Völkische Beobachter, for when they came to power. Also on the list was Bertolt Brecht and Klaus Mann. Goebbels had called for ‘putting writing scum up against the wall.’

Would Kerr and his family be able to stay in Berlin? In recent months, the 65-year-old journalist had been deeply uneasy and restlessly productive, penning one long article after another. As if his time were running out…

Hitler refused all options that didn’t involve him becoming chancellor. When he didn’t get his way, ‘the Führer broke off the negotiations and flounced out of the room.’

The last days of January, there ‘was an orgy of backroom politics not seen since Wilhelm II,’ wrote diplomat Harry Graf Kessler.

Caution! Wet! Paint!

Saturday, January 28, 1933: Alfred Kerr was at the theatre at a premier of a comedy titled ‘Caution! Wet! Paint!’ by the Frenchman René Fauchois. Kerr had heard the political rumblings, but his bags ‘were not packed, he’d stashed no money abroad. His valuable collections — first editions of Heinrich Heine… were scattered across the apartment in all their glory. If the Nazis did seize power… there’d be time to sort everything out.’

The Führer was moody. He railed into a monologue against the whole lot of ‘vons’ — ‘his entourage had heard it all before, listened in silence, supplying the audience Hitler needed.’

The next day, Hitler and Goebbels were drinking tea when they got the news the matter was settled, ‘they sat alone in silence for a long time, then stood up and shook hands.’

“Even when they were alone, the Nazis had a weakness for theatre.”

Monday, January 30, 1933: After 56 days in office, von Schleicher stepped down and despite assuring high-ranking members of the military on January 27 that he’d never make Hitler chancellor, von Hindenburg did just that.

Hitler was chancellor.

A photo was taken on that day of 11 men, among them, Hitler, Göring, Goebbels, Röhm, Himmler, Hess, and Frick.

Murder Inc.

Rumors of a military coup made their way to von Hindenburg’s office.

“Nobody on Hindenburg’s staff checked whether this was true. Instead, they listened anxiously for the sound of marching boots…”

****

****

Bette Dangerous is a reader-funded magazine. Thank you to all monthly, annual, and founding members.

I expose the corruption of billionaire fascists, while relying on memberships to keep the light on.

Thank you in advance for considering the following:

Share my reporting with allies

Buying my ebooks

A private link to an annual membership discount for older adults, those on fixed incomes or drawing disability, as well as activists and members of the media is available upon request at bettedangerous/gmail. 🥹

More info about Bette Dangerous - This magazine is written by Heidi Siegmund Cuda, an Emmy-award winning investigative reporter/producer, author, and veteran music and nightlife columnist. She is the cohost of RADICALIZED Truth Survives, an investigative show about disinformation and is part of the Byline Media team. Thank you for your support of independent investigative journalism.

🤍

Begin each day with a grateful heart.

🤍